“I would like surfers to say: ‘I’m not going to wear neoprene because people are getting poisoned.’”

An interview with surfer, photographer, filmmaker and activist Lewis Arnold from the north-east of England

“I would like surfers to say: ‘I’m not going to wear neoprene because people are getting poisoned from it.’ People who would never dream of owning a wetsuit. They wouldn’t have the money and culturally, it’s not on their radar at all.”

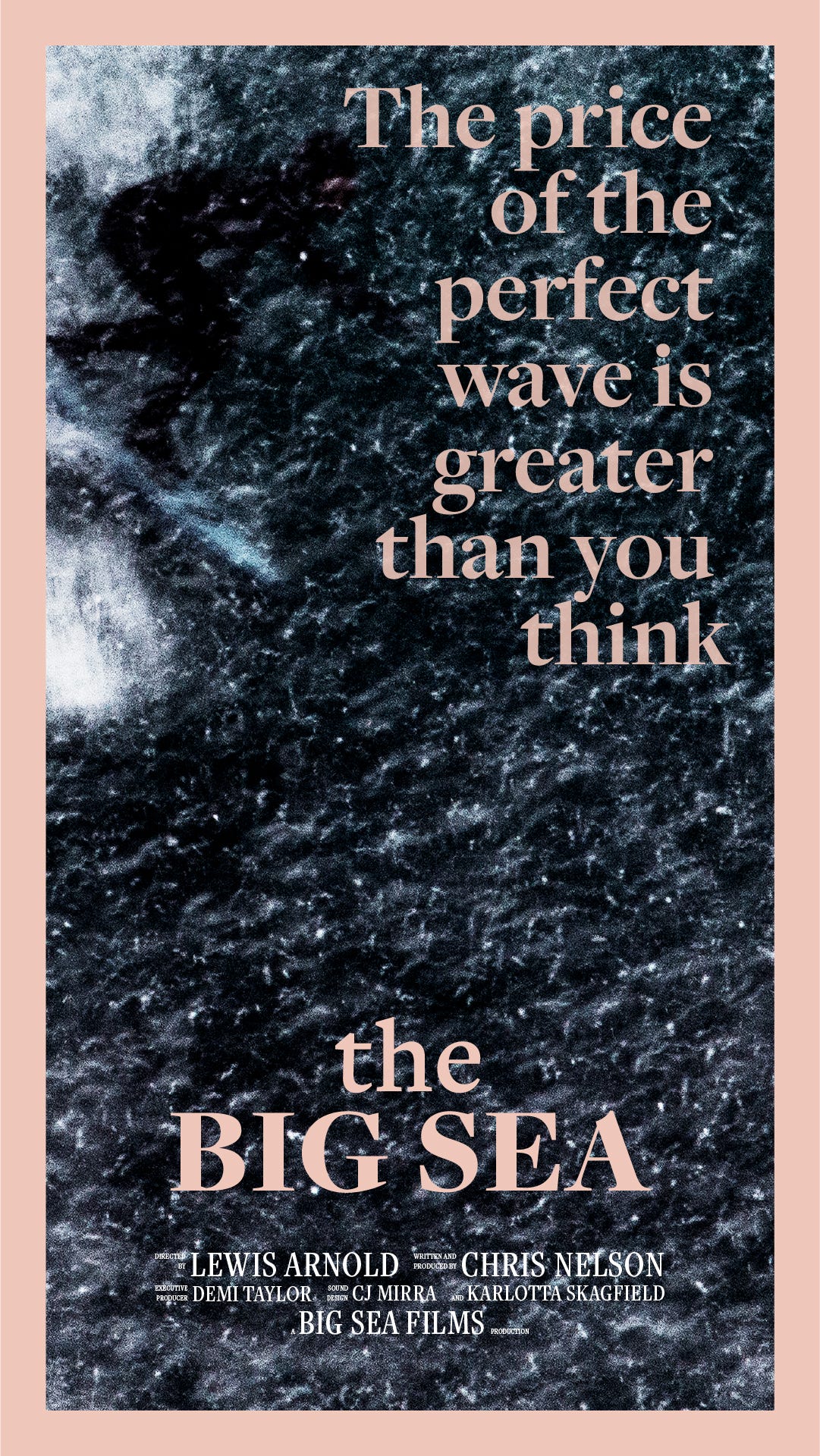

Lewis Arnold has long been chronicling wave riding in the north-east of England through his atmospheric and atypical surf photography. Before the pandemic, he started digging into a story of environmental racism in wetsuit production which should shake the surf industry to its core. The resulting film, The Big Sea, which he directed, is previewing at the London Surf Film Festival this weekend and it’s definitely worth checking out.

I first met Lewis back in April. He’s a great guy and you can tell that making this film has been an intense and very personal process for him, which we get into a little below. I hope you enjoy our chat.

Hey Lewis, how’s the surf been lately?

It’s been quite a slow start in the North Sea. We’ve normally had a really good swell by now but aside from a few single days we haven’t had much, and it’s been weirdly warm. But that’s not really been my focus recently.

Yes, you’ve directed a new film, The Big Sea. How did it come about?

An ex-colleague sent over this piece from the Guardian on Cancer Town, as she knew I was a surfer. The article is about Reserve, a town in Louisiana where the risk of cancer is 50 times the national US average due to toxic emissions from a chemical plant that produces chloroprene, the main ingredient in neoprene. It’s been owned by Denka since 2015 and the plant has produced the main raw ingredient used in most of the world's wetsuits since the late 1960s.

I was amazed no one in surfing had picked up on it. I’ve surfed most of my life and owned many wetsuits, but I’d never heard of chloroprene until then, so I started looking into it. This was just before the pandemic; I was doing a Masters in Creative Photographic Practice and looking for ideas for my final project. I went over to Reserve, knocked on doors, chatted to locals and made a photo essay and film about it, which I then sent off to a couple of film festivals.

Chris Nelson and Demi Taylor, who run the London Surf Festival, offered to help produce the film so we could reach as wide an audience as possible. It’s retained a lot of my visual style, which runs through my surf photography, it doesn’t look like an ITV documentary or anything like that. The subject matter is heavy, but I think people will enjoy watching it.

As a surfer, how did you feel about the harm wetsuit production had been causing?

I felt duped. I couldn’t believe that Denka, this company which I’ve been backing by buying all these wetsuits over the years, was making loads of money out of surfing, and causing all this damage. But really surfing has been complicit too.

Neoprene is used in a lot of other industries, such as automotive and tech. I’d expect them to be bad, yet the car and tech industries are actually looking for alternatives and drilling down into their supply chain and sourcing ethical raw materials, but the surf industry, I think a lot of them honestly don’t even know where they get their stuff from. I was interviewing people for the film and sometimes I knew more about their supply chain than they did.

That’s depressing, especially as surfers are often held up as environmental stewards to some degree…

Yes, but there’s been no need for the industry to change anything. They’re making money off it as it is so why bother changing but surfing is at risk of getting left behind as it’s not addressing its supply chain and environmental impact, while other industries are.

Some companies, such as Patagonia, Finisterre and SRFACE are using Yulex, the FSC-certified natural rubber as an alternative to neoprene. Are you optimistic about that?

Yes. I’ve worn a Yulex wetsuit in the North Sea for the past five years with no problems at all and through the research for the film I’ve been told by people that some of the best surfers in the world who don’t appear to be wearing Yulex are actually wearing Yulex. They say it’s gotten as good as anything else on the market.

Yulex is FSC-certified which is absolutely essential to avoid child labour and deforestation issues. They use smallholders in various parts of the world and help them get FSC-certified in a cooperative way as it would often be too expensive for them to do it individually.

The industry might be on the cusp of changing. I’ve noticed the language has changed when companies are advertising wetsuits, they don’t say neoprene anymore. And there are a lot more companies looking at Yulex, some as a tick box when 95% of their range is still neoprene, but I think that will change as Yulex is scaled up and gets cheaper. That will help the average surfer as the cost can be a bit of a stumbling block.

This summer, you went back to the US to visit the locals in Reserve again, how are they doing and what’s been their response to you making this film?

Residents have known for years they had elevated risks of all sorts of diseases. There’s a group called the Concerned Citizens of St John, who are in the film, and they’ve been super effective in their campaigning but the company they’re up against are experts in disinformation. They have massive wealth, they lobby politicians, and they’ve employed a Norwegian legal firm which once worked with Philip Morris to say that Marlboro lights aren’t bad for you. They use those kinds of tactics.

At first the locals wondered why it was up to a bunch of surfers to do something, why wasn’t their government protecting them. There were dirty tricks involved and during Trump’s presidency he was repealing environmental protections but since Biden has been in government the Environmental Protection Agency seems to be looking into it more. I read the other day the EPA are trying to make the company rehouse the kids in the school right next to the plant, so things are happening.

You also spoke to some key figures in the surf industry about the issue. Who stood out from those chats?

Jamie Brisick was good because he’s a former pro surfer and respected surf media figure. He said he’s thankful for wetsuits as they’ve enabled him to surf all over the world, but he admits he’s never thought about where they come from or what they’re made of. He’s also edited big surf mags but he says he’s never had his editorial stance dictated to because of advertising. But I have emails from people saying they won’t cover this issue as they don’t want to upset their advertisers. [I also experienced this back in the Cooler Magazine days.]

It’s tough in surf media, I’m concerned about it. People might ask what I’m doing? But I would say we do need an abrupt change in the surf industry on this. People have known about it for a long time, and this factory has been causing cancer amongst one of the poorest black communities in America. It’s environmental racism.

They’re putting the profits of surf companies ahead of the lives of the residents who are 95% black. The area itself is all former slave plantations, these people are descended from slaves and after the abuses of slavery they’re having to deal with the abuses of the industrialised world.

There’s neoprene in lots of stuff, as you say. Why is it important that surfers stand up to this?

The original thing that got my back up was when I went on Denka’s website, and next to the big president’s statement they brag about neoprene being used in wetsuits and facilitating surfing. They were hijacking surfing to greenwash a load of toxic product. And when you hear the word neoprene, even as a non-surfer, you think of wetsuits.

I would like to use the cool and visibility of surfing in a positive way, for surfers to say: “I’m not going to wear neoprene because people are getting poisoned by this.” And these are people who would never dream of owning a wetsuit. They wouldn’t have the money and culturally, it’s not on their radar at all. They couldn’t believe that people would buy a product that is killing people just to have fun. Some people might argue otherwise but it’s not like surfing is a matter of life or death. It’s a sport, it’s R & R.

The Big Sea is previewing at the London Surf Film Festival this weekend and Lewis is doing a Q & A with the film’s producer Chris Nelson, hosted by my good pal Matt Barr, who does the awesome Looking Sideways podcast. Head here for tickets and to watch the trailer, and find out about future screenings here.

And this is a cool piece on surfing in the North Sea, with stills and a short film shot by Lewis.

Other news:

On the subject of Looking Sideways, I loved Matt’s book, including Owen Tozer’s beautiful photography, in case you’re looking for Xmas present ideas.

Our water bill came through, so we’ve now joined the Southern Water payment boycott (which I wrote about in the second half of this piece). We’re still paying the water part of our bill, just not for the wastewater treatment. Given the beach I surf at has had 55 sewage pollution alerts this year (and the local swim beach 24) that seems more than fair. Interested to see how the Good Law Project cases against water companies go too, as Surfers Against Sewage’s latest water quality report for 2022 does not make for encouraging reading.

Please fwd this newsletter to anyone who you think might be interested & if you have any story tips on any of these themes pls get in touch.

I was lucky enough to see the film and watch / listen to Matt's interview at LSFF this year. It was amazing to watch with a crowd of like-minded individuals, and a pretty special moment to see the reaction of the 'consumers' in the room. It's a story that needed to be told and has been told in such a considered and well structured manner, with Lewis' film making and documentation, and the way in which Chris recognised gravity of the subject, the importance of the message and the need to tell more of the story. Great great work! Let's hope this can be a catalyst for change. There is no reason to continue to pollute and kill when there are alternatives to the use of neoprene. Once you have watched this film you will never buy a neoprene wetsuit again.