“No one wanted to surf when the bulldozers were destroying the village.”

An interview with Younes Fizazi, surfer, photographer, and former homeowner in Imsouane, Morocco

“During the destruction of Imsouane, the waves were some of the best we’ve had all winter… but no one wanted to surf when the bulldozers were destroying the village and the military were all around. I could not paddle out when they had destroyed the house of my neighbour and were about to destroy my house.”

Early this year, in the second week of January, I was lucky enough to head to Imsouane in Morocco for a travel piece*. I’d never been before but I’d heard only good things about this mellow fishing village with its magical, peeling right hand wave.

I had a genuinely awesome trip – met some lovely locals, caught some of my best ever waves, and really enjoyed the laid-back spirit of the place – then, a week after I got back, swathes of the village were razed by the Moroccan authorities. It prompted outrage in the western surf community (read more here, here and here), but I thought it would be interesting to speak to a Moroccan who was directly affected, so here is an interview with Younes Fizazi, whose troglodyte house in Imsouane was destroyed last month. I hope you find his perspective as insightful as I did.

Hey Younes, how are you doing?

I’ve been surfing my brains out these past few weeks because it was my way of forgetting about everything that’s been happening in Imsouane. I’m not there now, I’m currently at a beach, near Rabat, the capital city. When there was nothing to save anymore in Imsouane I left.

What’s your history with the village?

I first went to surf there in 1996. I’d heard about Imsouane, this crazy long wave in a fisherman’s village in the south of the country. At that time there was only 100km of highway in the whole of Morocco, and to reach Imsouane it was 600km of driving – it took us 14 hours without stopping.

What was it like then?

It was another Morocco, not the Imsouane you know. There were no new buildings or lighting or electricity, it was just fishermen living there, surfers didn’t really know about it yet. I spent 10 days surfing the bay alone, as my friends on that trip were not surfers. It was the first time I’d surfed a long wave like that, I was 19 and it was at the beginning of my adventures in Morocco. Now I have surfed along most of the Atlantic coast in the country but at that time it was a dream.

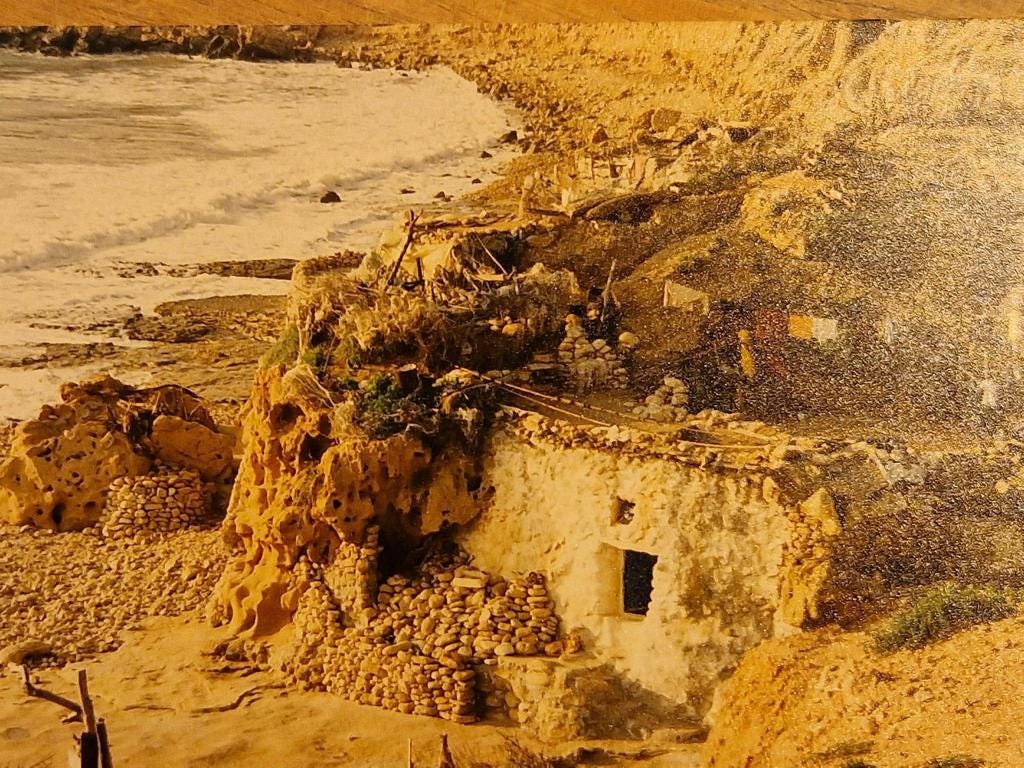

Besides the wave, the scenery, and the way the village was, it was wild, and the only buildings that existed were the harbour with its tiny grocery shop & coffee shop, a place where bread was cooked, and less than 10 tiny troglodyte houses around the river mouth. That place was called Tasblast, and my ex house was one of those troglodyte houses.

I shared some photos recently on Instagram of my house from 1984 (above). I can’t get the exact date of when the house was first built, all I know is the man who built it had survived the Indo-China war, so sometime in the 1960/70s. I’d been renting it along with the other little houses since the mid 90s and I bought it in 2020.

Some people referred to the houses as Berber settlements, is that the right term?

Yes, Berber or Amazigh would be better. The proper word to refer to that population is Amazigh. When I first came to the area, surfing was not a way for them to make a living. There were no settlements in Aftas Imsouane, it was just a fisherman's village. The population lived and still lives in the three little villages uphill. At that time, people from those villages were coming to Aftas Imsouane to fish or purchase fish mainly.

Surfers from other spots in Morocco were the first ones to surf out there, very few foreigners came to Imsouane at that time. For people from the north of Morocco like me, Imsouane was way warmer in winter. Imsouane, Taghazout…we called it the south, we’d say: “Let’s go south.”

When did it start to become more developed?

By around 2005 there were more westerners coming but still just backpackers and surfers who wanted to be off the beaten track. But around 2015, surf camp tourism started to boom, including more yoga retreats and people who had money who needed more comfort and with that came a new offering.

I bought that house which was not supposed to be my house, but a business, and I started to surf less here. Surfing with 300 other people and not being able to follow my own surf line was not really my thing. And by then it wasn’t something that was wild and clean or preserved or pristine.

My house was supposed to become a legal hostel, as I had asked public authorities to rent the land to the company I created for that purpose (as in a procedure to respect the Moroccan law). But most other houses in Tasblast were rented illegally. Cash was flowing without being taxed. Even though these places were listed on Airbnb and booking.com not a single dirham was declared.

Morocco has a big problem with the use of cash, as many Moroccans are still out of the banking system but the country obviously wants a tourism sector where the money that would come from Imsouane's taxation could benefit its finances too.

So, they said: “Ok, let’s raze every little house and business that doesn’t have the right papers.” And it was a violent enforcement of the law. People got just 24 hrs of notice, whether it was a house or a business. I was on a surf trip very far away, I came back 48 hours later and my house was still standing but most of Tasblast village had gone.

How did you feel at the time?

I was shocked when it happened and sad for me and the poor people who lost those houses, I was quite hysterical, but with time I realised that we don’t have much to complain about because the houses were not ours, even if we built them, because we knew it was government land, special land that is called public maritime domain and it can’t be sold or rented from the government to a person.

The government chased us from our places, but they didn’t fine us for the backdated taxes, it could have been a lot worse since we were not considered to be occupying the land legally.

But I speak for myself, some local families claim to have been owning those houses and lands for a very long time. My case is different. I wanted to keep the patrimony, because of the heritage. They destroyed about 80 houses, but I think around 80% of those were built in the last five-six years but five or six of them were old traditional houses like mine.

I think they should have saved the older houses, the ones that kept the original style, with white limestone walls, wooden pergolas and all that. I believe it was a big mistake, if they didn’t want us to occupy them legally, they could have turned them into an art gallery, coffee house or restaurant, and all the money could have gone to the village development.

The newer illegal houses were built with concrete, not in the traditional way, and people were often not respecting the sanitation. There was an obvious sewage problem to deal with out there.

I did get a whiff of sewage at low tide when I was there…

You should have come in summertime, when the sewage was literally flowing in the dry riverbed, it was horrible. I would never go there in July and August, could you imagine you had a house and could not go there in summer because of the sewage? I was begging my neighbours to let me help them fix the sewage problem, because what they were doing wasn’t viable.

And what do you think will happen next? Will they build luxury hotels like the ones south of Taghazout with the huge water-intensive gardens?

No nothing will be built where the houses were destroyed, they have decided that these places will be a walkway by the ocean, so ok why not? They’re going to build higher up around the camping spot.

Should visitors keep coming to Imsouane?

People should come, at least to support the locals who are still there.

What about the nice man who used to bring his horse to Imsouane and house him in that makeshift stable?

Said and his wife Zahra? No, their house and coffee house were destroyed too. The poor guy, he was nice and his wife as well. There are so many people who lost everything. The government had been closing its eyes for 20 years, but it seems like this is the end of an era. Will something positive come out of this? Time will tell, and I want to remain optimistic. All I wish for is inclusive development.

Is the hope that people can find jobs in other ways?

I hope more than that. I hope the government will try and create a little new centre in Imsouane so that these people can be legal. Especially those businesses that had legal papers and were renting off the local commune. Businesses like Anzar and the mini market, they should gather together and ask the government to find some land in the village where they can build other shops which they can rent and pay their taxes legally.

But people should still come as most of the village is still there. It is really the old part where I was in front of Cathedral Point which has been razed and some of the shops and businesses that were in the centre.

Were people still surfing when the demolition was taking place?

What’s crazy is that during the destruction of Imsouane, the waves were some of the best we’ve had all winter, there was an ultra-big tide and it was firing. For three-four days I was watching Cathedral Point and these perfect, glassy, off shore waves were peeling from top to bottom but no one wanted to surf when the bulldozers were destroying the village and the military were all around. I could not paddle out when they had destroyed the house of my neighbour and were about to destroy my house.

But it was also like a message from the ocean: whatever happens I’ll be here and I’m more powerful than all of you, the ones who cry, the ones who destroy… it was a reminder that all this that’s happening is small compared to nature. Imsouane will always be there, it was there before us and will stay when we don’t exist anymore, it will survive everyone.

You can follow Younes here.

*Whether I should be taking surf trips that involve flights and encouraging others to do so remains an unresolved question in my head, though I don’t do it a lot and when I do I’m careful to spend money with local businesses to avoid tourism leakage.

Other news:

The BBC’s Ski Sunday did a good feature on how the climate crisis is impacting snow sports last week including a guest appearance from the awesome ski guide and ecologist Brad Carlson, who I’ve worked with before, and a ski race result completely upended by warming temperatures on the day.

And Outside Magazine looks at the effect of global heating on extreme freeride skiing and snowboarding events here.

Big ups to the Wandering Workshops team for this lovely short film about splitboarding.

And Patagonia for their campaign to protect wild salmon in Iceland. I no longer eat farmed salmon and I think if you watch Laxaþjóð | A Salmon Nation you’ll feel the same and also super angry to see yet another example of extractive capitalism destroying a local ecosystem.

See also the UK water companies. I love SOS Whitstable (read more on their key role in the sewage fight here) & think their Sirens of Sewage sculpture is incredible.

I enjoyed interviewing Vasu Sojitra, founder of the Inclusive Outdoors Project, about the best accessible ski resorts in the US, and the ultra runner Tom Evans on running extreme distances with unprecedented pace.

As ever, please fwd this newsletter to anyone who you think might be interested & if you have any story tips on any of these themes pls get in touch.