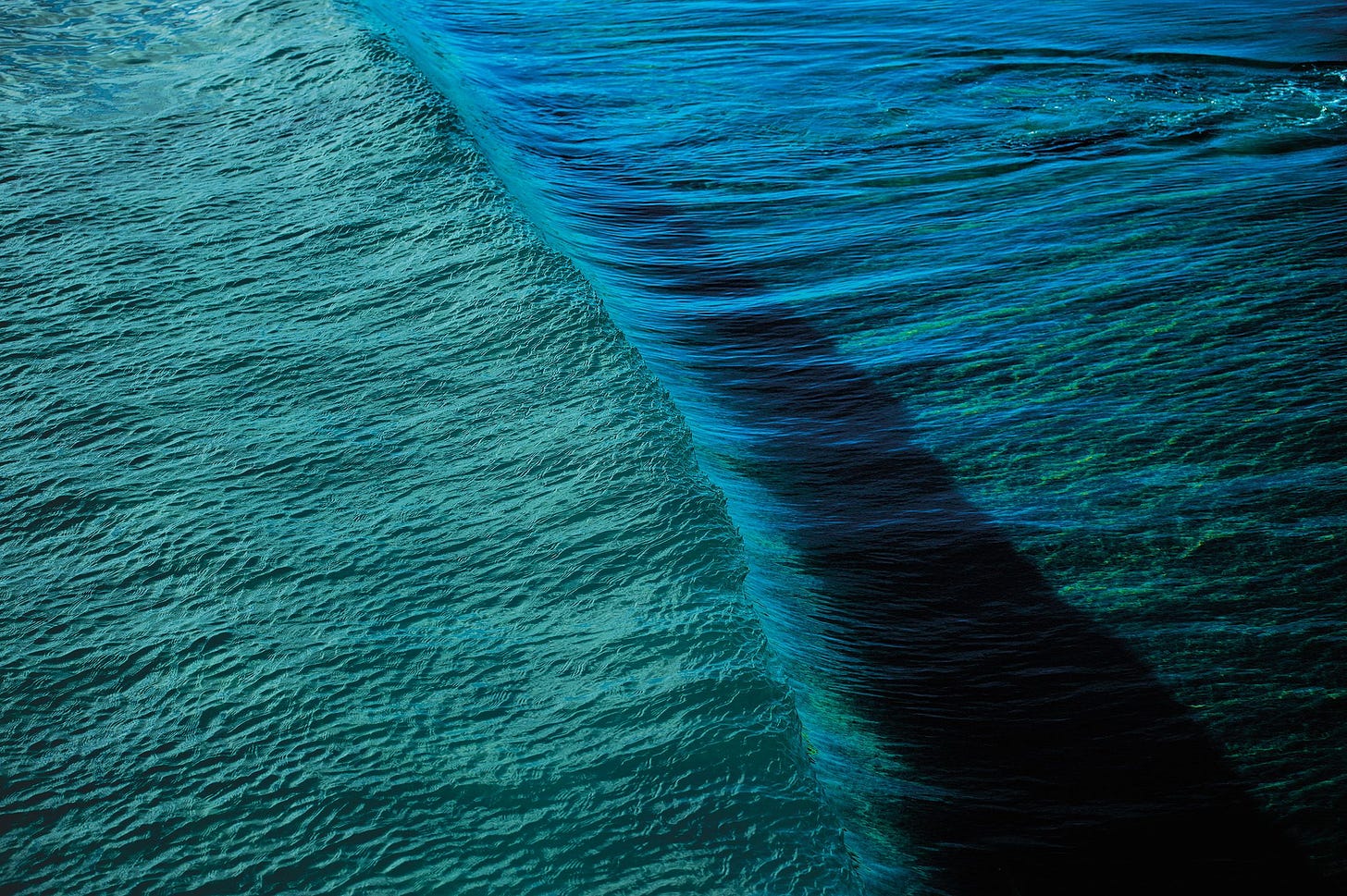

“We don’t take care of the ocean like it takes care of us.”

An interview with Léa Brassy, surfer, freediver and environmental advocate from SW France

“We don’t take care of the ocean like it takes care of us. Since I was a child, it’s really taken care of me so it’s like when someone you love gets sick, it hurts inside, it’s that same feeling.”

I first met Léa on the Patagonia Surf Impact camp last spring, and we connected again recently in Talamone, Italy, when I was doing a story for Huck Magazine on why we need to ban the destructive fishing practice of bottom trawling (it’s often described as taking a bulldozer to the ocean floor, which destroys everything in its wake).

Léa uses her platform as a pro surfer, and now freediver, to amplify environmental issues, such as bottom trawling, sewage, building artificial wave parks, and the impact of the Olympics in Tahiti, as we’ll get into below. Her passion is an inspiration and I hope you enjoy this chat.

Hey Léa, how’s the surf been lately?

June in France has been very slow so far in terms of waves… I can’t wait for a new push of swell!

We met up recently in Talamone to find out more about the impact of bottom trawling on marine ecosystems. How does surfing relate to these conversations?

Surfing is about finding balance, both on your board and metaphorically in your own life. We can only do it because the ocean is alive, it has a breath of its own, but it doesn’t have the same energy without marine life.

There’s no surf in a dead ocean, right?

Yes, the seaweed, the smell, the energy that comes into play when you’re in the ocean is all part of it. And you notice it so much more where it’s under threat from pollution or overfishing, which both affect marine life.

In France, the water can be smelly, especially after it rains, there is plastic waste, human waste…whereas I’ve surfed in environments, such as Chile, where there are birds everywhere, sea lions, so many good sized fish, with their mouths delicately coming to eat the top of the surface, and huge seagrass meadows to nurture them. I was so impressed to see areas that are healthy and thriving as a surfer, with marine life living fully. Freediving underwater in French Polynesia was the same, the difference between that and France is incomparable.

We don’t take care of the ocean like it takes care of us. Since I was a child, it’s really taken care of me so it’s like when someone you love gets sick, it hurts inside, it’s that same feeling.

How do you feel about being involved in Patagonia’s ocean protection campaign?

I’m super proud. Rather than just thinking about what’s wrong, we can transform that concern into positive action and do something effective. Working directly with the NGOs (such as Oceana, Bloom, Client Earth…) on the legislation and enforcement, it can’t be taken lightly.

How did you get involved in the campaign to prevent a local artificial wave park being built in Saint Jean de Luz, near where you live in SW France?

The project of the wave park in Saint-Jean de Luz had been a rumour for a while, but one day I saw a facebook post about it becoming a reality, and an action against it being built. I contacted the group and got in touch with the collective Rame Pour Ta Planète.

Learning more about the project, I had a growing feeling of bitterness that my passion of surfing would be used to sell this capitalistic thing, especially in my backyard. I wrote a letter, titled “Not in my name” to outline my values as a surfer, and why I didn’t want to be associated with such an anti-nature project. The collective read my letter and decided to use it as the focus for their communications efforts. 1800 surfers signed it in a month, including some big names. It was a tool for people to say no by expressing the core values of our sport, and it appeared to be a turning point in the campaign against the park.

What were your main objections?

Surfing is a school of life, with the power to raise awareness of the living world. It depends on nature and shouldn’t be considered as an activity where we can just use our credit card to generate a wave.

Our children deserve to experience the wilderness of surfing in the ocean, as freedom is the essence of surfing. We’re at a critical moment in terms of environmental health and climate change and there is no more room to concrete over what remains of the natural world.

What other environmental threats are a concern where you live?

Water pollution is a major one. Our water treatment plants are insufficient for the growing population and growing tourist industry.

Building concrete constructions over natural land that will no longer be cultivated for food or left wild for biodiversity is also a major one, as there is so much pressure from real estate.

And fisheries, with stock-threatening practices, such as what happened off the coast of Ondres in February 2023, when an enormous amount of huge “Maigres” spawners were captured in what was called a miraculous catch but was in reality a shameless use of GPS tracking.

Do you feel like surfers down there are becoming more environmentally engaged gradually? Or is there a lot more work to be done?

There is a lot more work to be done to be honest. The line-up reflects our society. There is hope, but also lots of people wearing blinders to keep things the way they are.

You mentioned some concerns about next year’s Olympics holding the surfing events in Tahiti, could you expand on that a little?

Tahiti is the home of Polynesian Culture. Society there was originally organised in a very different manner than it is in the west. Beyond protection, it needs acknowledgment and respect for its own way of life. There is so much to learn from this culture, especially when it comes to treating nature, and the island is not set up to host a big event such as the Olympics.

The Olympics come with lots of needs that seem normal for the western world (competitiveness, high speed internet, hotels, imported food etc…) but these are questionable needs in a part of the world that still holds hope for a healthier relationship with nature.

Could you talk a bit about your passion for freediving?

The ocean has always been meditative for me. Watching the horizon line from a young age is a strong memory of my good times in the water. But it’s hard to catch waves these days if you’re too meditative in the line-up. Meditation and freediving are interconnected. You need to find that meditative spot within yourself to perform a dive. It’s a very different approach than most surfing conditions, although maybe in more challenging conditions, it may have similarities.

For more on Léa head to her website, or Instagram.

Other news:

Protect the ocean so it can protect us. Patagonia has launched a super-important campaign to ban bottom trawling in marine protected areas. Read all about it, watch the videos & sign the petition here.

If you enjoyed my April interview with Dr Easkey Britton, she did a great Q & A with

on Looking Sideways this week.When I was googling whether freediver was one word or two (no consensus…), I came across this obituary of the Italian freediver Enzo Maiorca. Worth a read if you ever enjoyed the movie The Big Blue.

I really loved the film The Eight Mountains, go and see it in a cinema if you can.

And finally, if you’re anywhere near Brighton, get yourself down to Sea Lanes, our genuinely awesome new 50m outdoor pool.

Please fwd this newsletter to anyone who you think might be interested & if you have any story tips on any of these themes pls get in touch.

Interesting views on wave pools there.