“It was like surfing in a toilet with condoms, poop and panty liners wrapped around your ankles.”

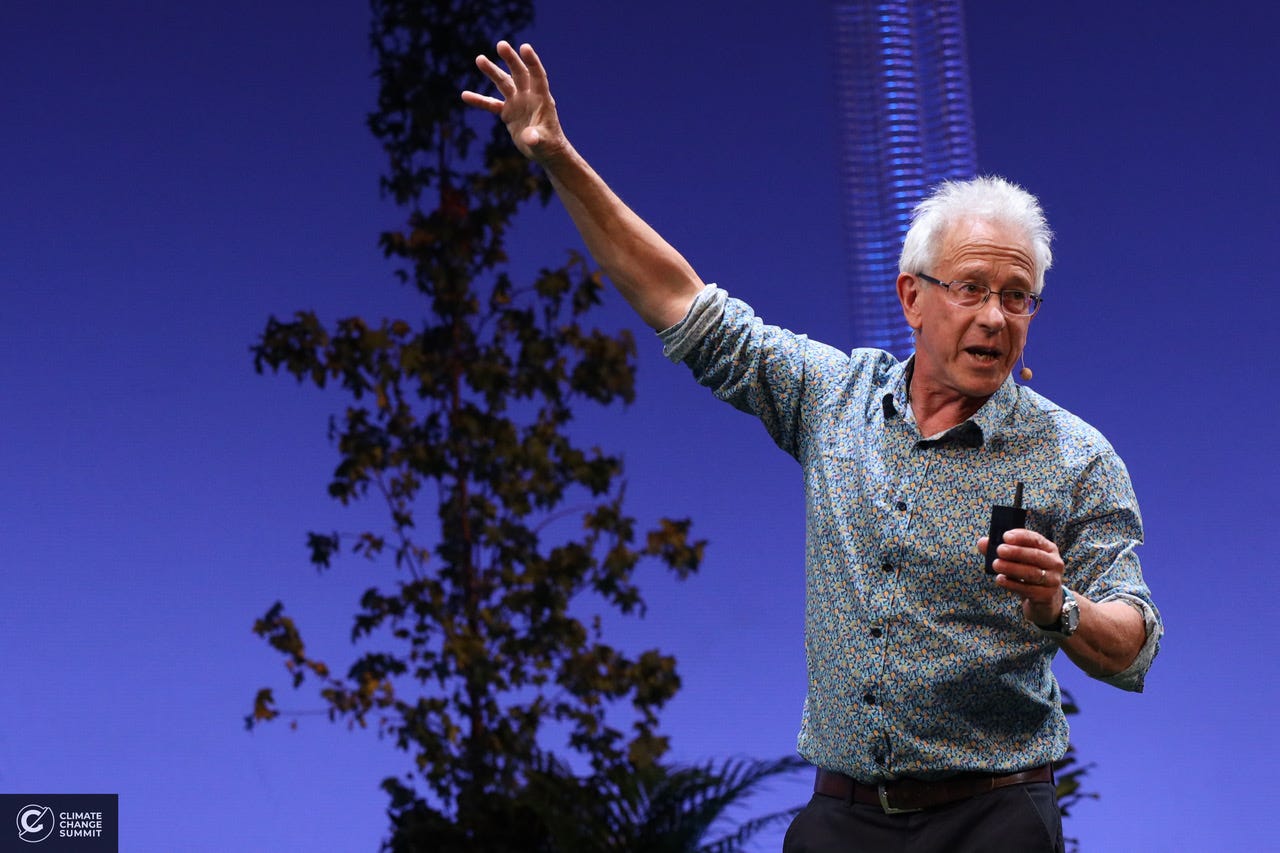

An interview with surfer and pioneering environmental campaigner Chris Hines MBE

“At high tide it was like surfing in a toilet with condoms, poop and panty liners wrapped around your ankles. The water fizzed from all the washing up liquid and washing powders, it was like a milky cream.”

This week, I’m proud to present an interview with the pioneering environmental campaigner and co-founder of Surfers Against Sewage Chris Hines MBE. Growing up in the suburbs of London, I only surfed a couple of times in the 1990s, but I knew and admired the work of Surfers Against Sewage and have done ever since.

It feels like there are many lines that can be drawn between the intelligent and visually-arresting actions of Chris and his friends back then and the work of environmental activists such as Just Stop Oil today. I hope you enjoy what I found to be a fascinating chat about campaigning now vs then, some of the pranks they pulled, and the issues raised by The Big Sea.

Hey Chris, how’s the surf in Cornwall?

Very nice. I went for a surf earlier in the week, though I’ve had to work since then. I did some media training for the new Surfers Against Sewage team and some consultancy work.

You co-founded Surfers Against Sewage in 1990. What was the campaigning landscape like back then?

It was a lot lonelier. We had Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace, and the Greenham Common protests, but the general level of environmental awareness and action was much lower. There weren’t many people who wanted to be involved. Communication-wise it was a lot lonelier as well. You had to phone someone, send a fax, or go and see them, or write a letter, we used to do a lot of that. There was of course no instant messaging or any of the network capability that comes with that.

In the 1990s, we had 18,000 paid up members, but there are pros and cons to both [eras]. It was almost easier to have that feeling of being part of a tribe then because people had to make slightly more of an effort to be a member of a group. You couldn’t just click to agree with something on your laptop.

If you look at the water sector now and the number of organisations who are campaigning in that space, it’s huge, whereas back then there was the Marine Conservation Society and us, that was the whole scene.

Why is sewage such a problem again?

There have been massive increases in population, but we haven’t continued to build the [sewage] infrastructure we need, and I think we’ve slightly taken our eye off the ball. We had that massive clean-up [in the 1990s] and since then other issues, such as the climate and biodiversity crisis, have arisen and taken over people’s attention.

Water companies have been bought by VC funds overseas, whereas they were all owned by privatised water companies in the UK before. We had shares in everything, and would do the rounds at everybody’s annual shareholder meetings with a protest outside.

An early example of shareholder activism?

Yes, we were doing that in 1991/92. I went into the Southern Water AGM as a shareholder with Andy Coleman [from SAS Brighton]. We had a toilet seat and were chasing the boss around with all the media to take a photo of it around his neck, but he wouldn’t come out and eventually they smuggled him out the back door.

Ten months after forming, we went to the Houses of Parliament and pulled the Secretary of State for the Environment and the Shadow Environment spokesmen into a debating room. There were 70 or 80 of us from around the UK, coach loads of people from Cornwall, Brighton, Wales, all congregated in a debating room.

How about in the water? Did you get sick a lot more when surfing back then?

I don’t want to undermine what’s happening now, as it’s definitely worse than it should be, but it was a lot worse back then. Crude [raw] sewage was discharged all day every day to the whole of the coastal population of Britain. Brighton had raw sewage, so did Newquay and virtually all of Cornwall, Plymouth had 26 different discharges going into the Plymouth Sound. There wasn’t even a basic screen in place so that’s why places like Porthtowan were known locally as ‘Porthtampon’.

At high tide it would be like surfing in the toilet of the largest conurbation in Cornwall with condoms, poop and panty liners wrapping themselves around your ankles. The water fizzed from all the washing up liquid and washing powders, it was like a milky cream. In Hartlepool, [crude sewage] from about 30,000 people would be discharging out of a pipe 50 yards from the promenade. On bad weather days it would bounce back, and they’d have to close the local primary school as it would be blowing onto the school playground.

Did you still always get in when the waves were good?

That’s just what it was like, and we were in a lot, but yes it was quite a common occurrence to get sick.

It was important for us to find solutions as well. It was cheaper to build UV treatment works as they had in Jersey than to build an outfall pipe out at sea, which is what the water companies wanted to do. At a House Select Committee, I said I’d feel safer sticking my head up Jersey’s outfall pipe [which had been treated with UV] than I would bathing on UK beaches and a week later Jersey’s tourist department invited me out to do just that. I got so far up the pipe I was blown out with the force of 100,000 people’s sewage but it did taste and smell cleaner than ‘Porthtampon’.

Today the water companies are given fines but they can make more profits even taking into account the fine, and they’re going to keep doing that unless they’re well policed, yet the funding to the Environmental Agency has been slashed so the regulators aren’t there.

In 1999, an eight-year-old died after coming into contact with raw sewage from a combined sewer outfall (CSO) in Dawlish. I was called to give evidence at the inquest at which the coroner warned that all CSOs should be clearly marked for the public. If it were to come up in another coroner’s inquest and they’d ignored those recommendations would there be grounds for corporate manslaughter?

And just because the government isn’t forcing you to stop doing something doesn’t mean you shouldn’t stop. At fossil fuel or water companies, haven’t they got their own moral compasses or standards of professionality and due diligence? Don’t they think about what the right thing to do is. If you get out of bed in the morning to work for a water company and think unless someone busts me, I’m going to keep polluting, there’s a bit of a void there in terms of understanding our world and where we need to go.

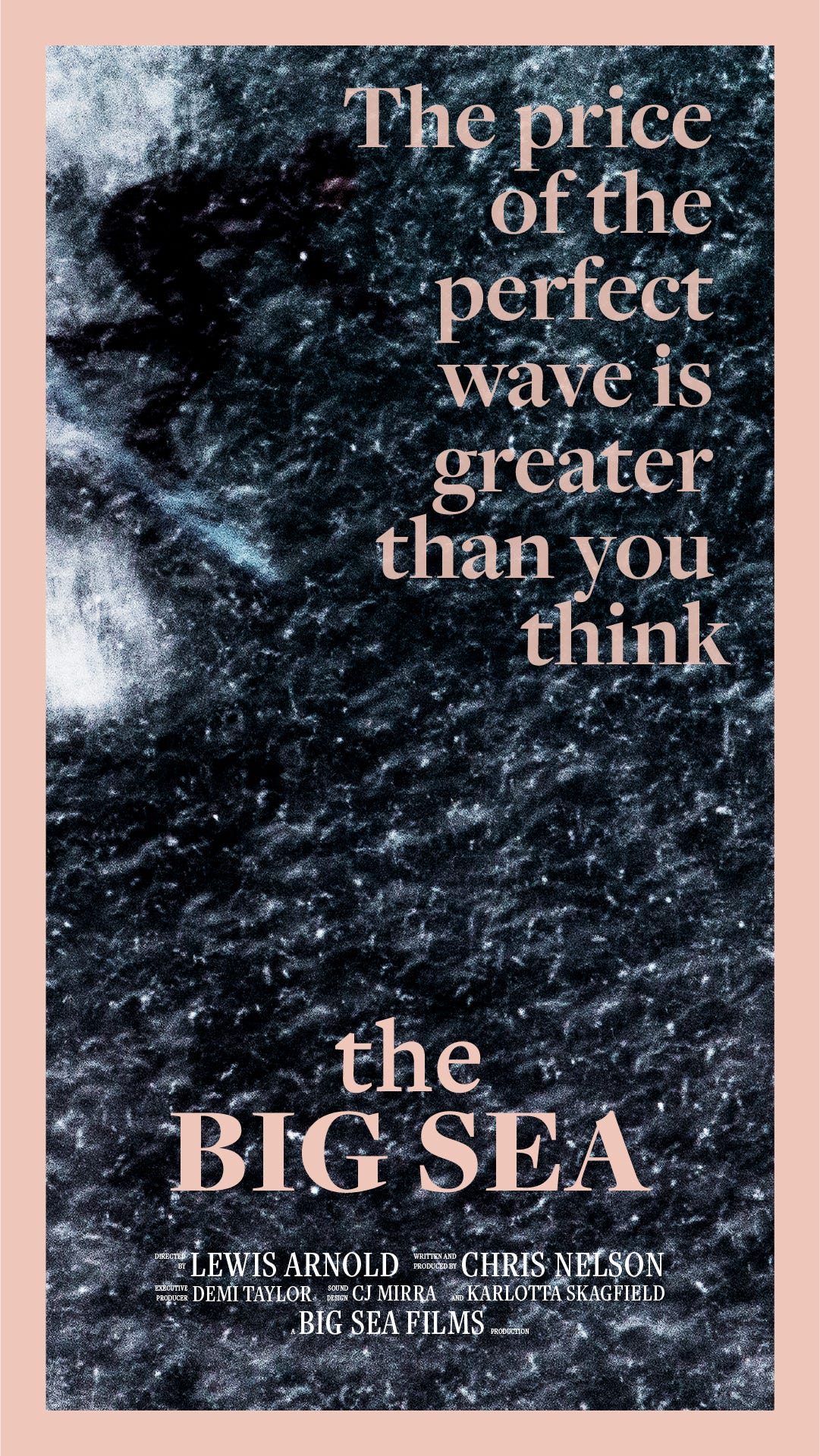

You’re interviewed in The Big Sea, the excellent documentary which lifts the lid on the toxic use of neoprene in wetsuits. For those of us who already own neoprene wetsuits, what should we do with them?

Wear them until they’re done, then repair them, but everybody should make the pledge that they’re not going to buy another neoprene wetsuit in the future. Make the action and then go into your surf shop or if you buy online tell the people you bought the wetsuit from that you won’t be buying another neoprene wetsuit in the future. As I say in the film, once you know you can’t go back.

There is a brilliant company in Newquay called Bodyline which repairs wetsuits. It’s probably one of the most sustainable wetsuit companies of the last 30 years. When I think about how many of my other suits have been kept going because of the repairs they did. If only we could scale that up around the country.

People might say it’s cheaper to buy a new one, but it’s only cheaper if you’re only interested in money. If you consider the great John Elkington’s thinking on the triple bottom line, where you think about the social and environmental bottom line alongside the financial one then it’s very cost effective.

I wish we had a Bodyline in Brighton. I have started getting things like jeans repaired locally…

Everyone should. This morning I put on a jacket for a smart work event and the lining popped out of the sleeve, so I turned it inside out and it took me five minutes to fix. Some people might have rushed into Truro to buy a new one, but it took five minutes and probably saved me £120. The world tells us we need new things, but we should repair them, and be willing to pay for the repair, as the person doing that needs to earn a decent wage.

Did you know about the problem with neoprene before The Big Sea?

Yes I’d read the article in the Guardian a few years ago but the film is brilliant, as I say in the film I think it’s the most condensed and brilliant piece of social and environmental campaigning by surfers ever.

Were you surprised the film was made by two surfers from the north-east and not California?

No because I think change often comes from the edges, where it’s a bit grittier. Why did SAS start in the UK? And why Porthtowan and not Newquay?

Other news:

If you’re interested in reading more about surf activism and the sewage problem, here’s a piece I did for Mpora last year.

For the Guardian, I wrote about Chamonix, the place where I fell in love with snowboarding, and how the resort and its guides are coping with the impacts of global heating. You can read the piece here.

A lot of brands do nothing for the planet, a lot of brands talk a good game, and then there’s Patagonia who have helped create an actual national park to protect one of Europe’s last wild rivers in Albania. Read more about it here.

Please fwd this newsletter to anyone who you think might be interested & if you have any story tips on any of these themes pls get in touch.

Love this Sam